Pani chaina, batti chaina, tel chaina, gas chaina (No water, no electricity, no oil, no gas): these are the common remarks that we have been recently hearing and experiencing quite intensely in Kathmandu. Demand for fuel and cooking gas is such that there is no queue that starts from the oil and gas distributors that doesn’t end in a serpentine manner to another end of the road. This has been a daily-life of the people of Kathmandu valley.

Worse is the demand for electricity since the unofficial Indian embargo which led to dramatic 14 hours power-cuts in a day. Due to over use of electricity (when available) has caused the transformer explosions in every neighbourhood in the valley.

This is the present scenario after the blockade, but how was it usually? Was it any better before? Well, no one would take second chance to scrunch their nose while answering these questions.

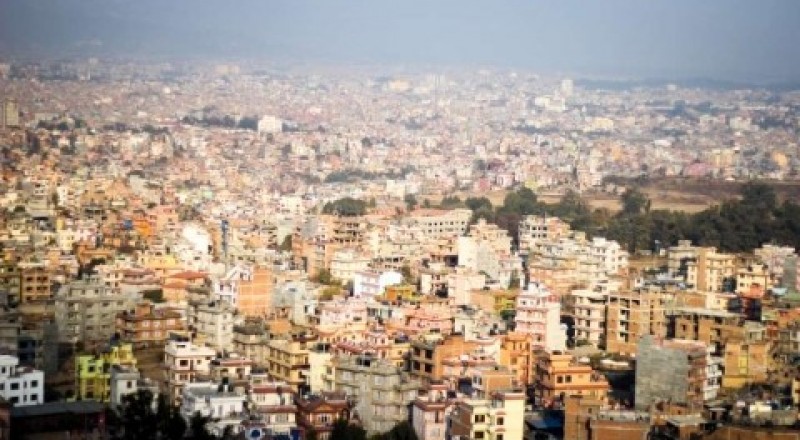

It’s becoming a concrete jungle. The Kathmandu city is one of the fastest-expanding metropolitan areas in South Asia. One can notice the building popping up in every inch of land. But a lot of this growth hasn't been planned or regulated. In the outskirts of the valley, satellite towns have grown without much guidance from the government. This has cost us thousands of lives in earthquake last year. Had we followed the building codes strictly, the extent of damage would have been minimal.

A rapid urbanisation in Kirtipur Municipality of Kathmandu. Photo: Uden Maharjan/HERD

With the uncurbed urbanisation came many inevitable challenges. The residents of Kathmandu have to wait for hours to get a pitcher full of water. Even the water they get after waiting for long hours is not safe and clean enough to drink directly and use in cooking purposes. Also, the ground water has depleted tremendously that the natural ponds around the valley have started drying up turning into a hard, cracked grounds.

A section of the Ring Road in Kathmandu fumed with the vehicle emission and dust. Photo: Uden Maharjan/HERD

Another common glimpse that we get without much effort to picturise the urban Kathmandu valley are the streets choked up with vehicle emissions, the dust dancing high in the air, and the narrow walking lanes, and the corners swamped with the piles of garbage lying ‘unclaimed’. No doubt that these invite unfavourable health issues. Unregulated motorisation coupled with unsafe roads have led to many road traffic accidents resulting in injuries and deaths. Also, streets often turn into an overflown bed of sewer during monsoon each year. Disappointingly, the holy Bagmati is not good anymore to praise its grace. Black sludge and streams of drainage poured down into the Bagmati’s water odorises the thin and soothing Kathmandu air.

Isn’t it empathetic to even imagine how the thousands of people are residing in the slums along the Bagmati banks when we are not even able to tolerate its nose-boggling scent as we swift pass by it?

All these, now, unfortunately, are the salient traits of the Kathmandu valley.

The Central Bureau of Statistics shows 4% of an annual urban population growth rate. The government’s inability to provide free health care puts millions of lives into the disarrayed health condition, particularly the urban poor – the proportion which is estimated to be at least 15 % of the total 27% urban population of the country’s 26.5 million people. These figures will hike if included the newly declared municipalities (making it 191 altogether). With a messy urbanisation, there is a widespread existence of slums and sprawls, particularly along the banks of rivers. This has given rise to the hidden urbanisation which is not captured by the official data. Such population density will only exert pressure on infrastructure, basic services, land, housing, and the environment – the congestion constraints that have been failed to be addressed considerably.

A slum settlement along the bank of the Bagmati River in Balkhu, Kathmandu. Photo: Uden Maharjan/HERD

All these factors add a huge pressure on the health system, too. The health care in urban areas is hugely dominated by the private sectors favouring the well-offs. A group of urban population of another end of socio-economic spectrum struggles sternly because of their inability to pay for the dear private health care services. Despite the government’s effort to provide essential health services in the municipal areas through the urban health clinics, it has proved to be very ineffective and inadequate. Limited service range, poorly resourced and sparsely located, these service outlets are way out of league to address the health needs of urban population.

So the question is: how can Nepal better manage its urbanisation to create more livable and prosperous cities?

The Nepalese policy makers and the government, face a choice to continue the same path or undertake difficult and appropriate reforms to improve the country’s trajectory of development. It won’t be easy but such actions are essential in making the country’s urbanisation sustainable making cities safe, secure and livable. This will only seemly appear when the government addresses the deficits in empowerment, sustainability, resources and accountability.

Furthermore, the areas of policy actions that would be instrumental to address the urban issue of congestion constraints and help leverage urbanisation to improve the country’s prosperity and livability would be: sustainability; connectivity and planning; land and housing; standard services and facilities; and resilience to natural disasters and the effects of climate change. For these, it requires more coordinated approach among the government and private sectors and increase public participation in the process of planning and resource mobilisation.

Comments(0)

No comments found.